Annual Letter from the Director

Annual Letter from the Director

Release Date: November 8th 2021

The theme of my address this year is – the burden of longevity.

As we usher in our second [2nd] year at the Noldor Residency, now indistinguishably recognized within the Institute Museum of Ghana, it goes without saying that I remain deeply proud of my team for their collective dedication to the artists we serve. Especially, but not limited to, our Chief Curator Rita Benissan, who finally moved from Michigan to fulfill her role at the museum having started remotely in the midst of the global pandemic.

It’s important to acknowledge some incredible milestones during our first year: A major one was hosting the recent LACMA Honouree and Founder of Black Rock Senegal – Kehinde Wiley. It felt wonderful to impart such an invaluable experience in which practitioners within the residency could engage in discussion with one of the most important living African-American artists of our generation. All through the support of the Creative Arts Council under the Ministry of Tourism, Arts & Culture in their affiliation.

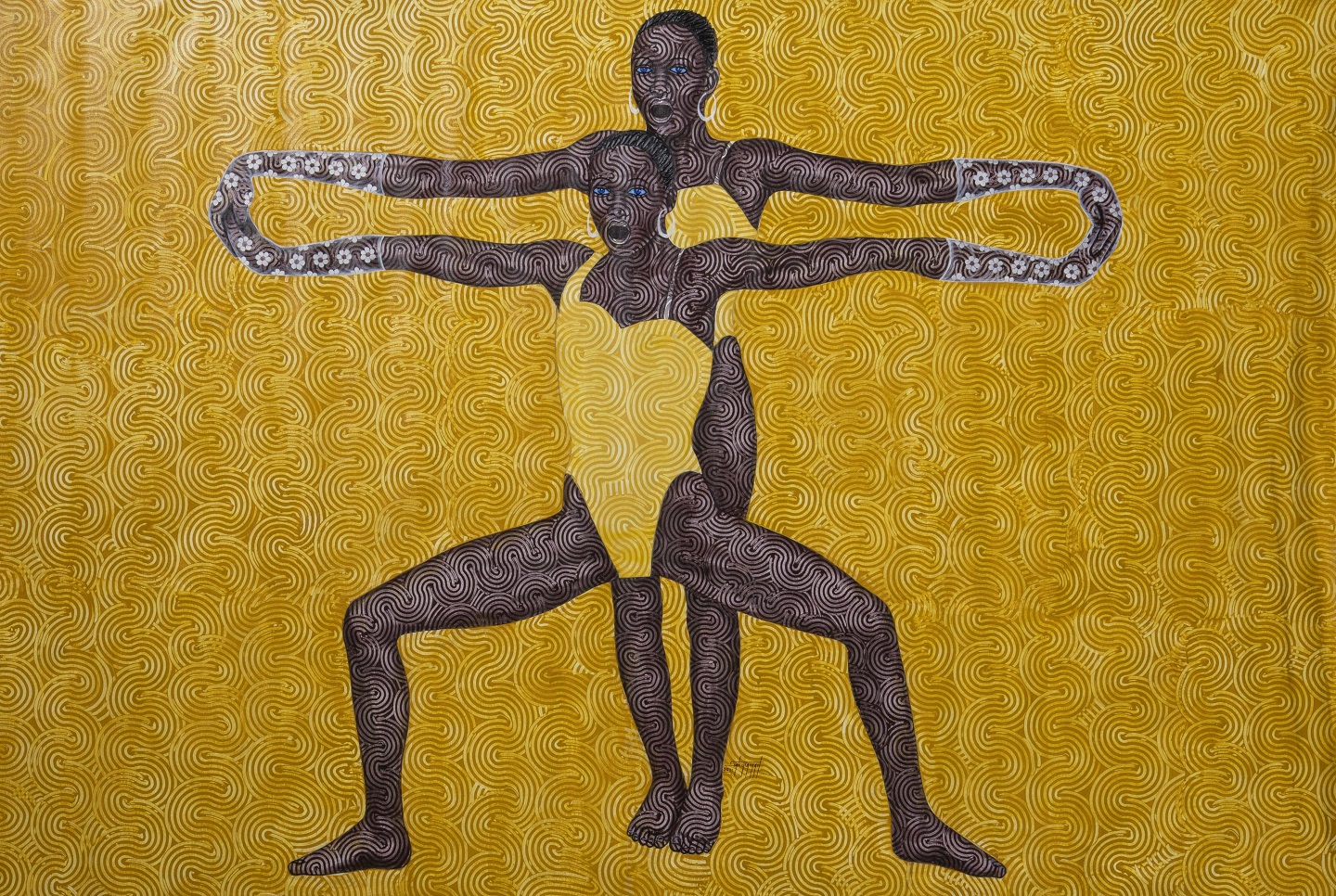

In my capacity as the museum’s founder, I have also been very happy to have donated a number of works from my private collection to the museum’s permanent collection of African contemporary art towards our public opening in March 2022. Donated pieces from my collection include works by Isshaq Ismail, Moffat Takadiwa, Modupeola Fadugba, Serge Attukwei Clottey, and Fathi Hassan.

The recent completion of Phase II within an extensive ten phase restorative and structural integrity-based efforts to secure our building has also been amongst our great milestones. Infrastructural expansion within the on-going restoration of our sprawling 7,200 sqm museum enclave to support more artists has been prioritized in the spirit of securing a safe environment for continued creative proliferation.

In our bid to be inclusive, supporting our inaugural Digital Fellow, Marcel Kojo Gyan, on a sponsored trip to the Mecca-like NFT NYC in New York this year was a great step in truly empowering often ‘othered’ digital artists who fall outside the use of classic mediums – especially on the continent.

Though I remain an adherent believer in the mantra of “art for arts sake”, I understood that contemporary art could not be created in a vacuum; art was always to be discussed, critiqued, examined, engaged and eventually placed. And so when I began the Noldor Artist Residency, I was adamant about instilling a proactive culture in the way our team offered collective support to artists. Given the near-meteoric track record of successes that artists from the institution have experienced, such as Emmaneul Taku, it has become evident that we offer what very few residencies offer in inculcating a commercial awareness. We do this while canonizing the artists we empower in order to navigate a real-time career trajectory – one that yields results.

Beyond the double-volume studio spaces, facilities, materials and studio management support at the residency, all artists additionally have a fairly generous stipend that exceeds more than triple Ghana’s National Service income. Furthermore, all artists have access to an in-house clinical psychologist, in-house legal council and fully sponsored immigration support if ever it is needed. We are happy to provide this.

A beacon of hope on the significance reflected in the empowering nature of commercial awareness for practitioners is Ibrahim Mahama. The artist’s awe-inspiring accomplishments in institutional thinking have resulted in the building of the SCCA, Red Clay Studio and the Lazarus Project in Tamale. Three ambitious Herculean self-funded initiatives by Ibrahim made possible with major capital generated from the sale of his monumental works through well recognized commercial galleries. He is sustained through this element.

Subsequently, as far as longevity is concerned, I increasingly find that there is nothing particularly interesting or noble about being underfunded and under-resourced. I find that idyllic (at times almost self-righteous) puritanism in the art world is often rendered futile in the face of pragmatism – the need to apply new models that work and sustain for specific parts of the world.

Using Ghana as the most applicable case-study, there is very limited / no access to government funding for institutions within the Arts & Culture ecology which means that quite often non-profit organizations are left with nothing more than a vision and a begging bowl. Ghana does not even have the equivalent of a 501-C tax benefits system that would encourage local donors. As such, arts-focused organizations in Ghana do exist but may have negligible transformative impact.

This is evidenced in the demise of the great Ghanatta College of Art & Design that now remains in its semi-derelict state of former glory. Having spoken directly with the former principal, Mr Kwame Boakye, it became increasingly evident that the lack of an endowment with no government intervention nor state supported resource mobilization resulted in the college’s eventual need to suspend practice. A modern tragedy for a space that remained a bedrock for so many aspiring emerging artists in Accra.

For this, amongst many other reasons, it is therefore tone deaf and fanciful to imagine that the same principles, models and belief systems that govern forming a residency or establishing a museum in the West would be exactly the same as on the continent. The need to be adaptive is therefore not opportunism but actually necessity.

With the accountability of a diverse board, the model through which a minimum amount of pledged works by emerging artists are deaccessioned to reputable custodians also means that proceeds go entirely towards repurposing and improving facilities at the museum. Programs are also developed with the right expertise engaged at the institution to better support the next generation of artists.

I have learnt a valuable lesson from all the discussions and queries raised given the novelty of the institution’s model – that in order to innovate one must first be willing to be misunderstood. I embrace this and remain further emboldened to do my part in securing Ghana’s cultural and creative future within its largely under served artist ecology.

With the support of my amazing team and the artists who have pledged in the spirit of “service above self” to this belief system, I am rather emboldened by the critical discourse and debate surrounding the commitment. I’d like to also express gratitude to all Noldor artists who have sowed a seed in Ghana’s cultural destiny through the works they have so far pledged. But I would like to especially recognize Mimi Adu-Serwaah and Foster Sakyiamah who have both fully completed their pledge of twenty-one [21] works to the institution within one year in the truest act of ensuring the longevity of the Noldor Residency that has functioned as a catalyst for their careers.

In leading by example, it is important to note that as an artist myself, I have completely pledged the entirety of my body of several works from my solo exhibition in February 2019 with the Gallery 1957 to the institution. However, I would like to encourage the dialogue surrounding the novelty of the artist pledge upheld at the institution to continue for that is how progressive-thinking truly occurs. All while noting that I am constantly learning and remain internally critical of how to forge ahead with the lessons we have learnt as a team.

To conclude – we press on into our second year giving special recognition to Deborah & Jacob Kotzubei and Roderick Belin whose major donors contribute towards our very needed longevity. But also to acknowledge all donors, supporters, curators and artists who have poured a bit of themselves into keeping us alive. Through the good times and challenging moments.

I’d like to end this address with my favourite quote by Sigmund Freud which goes “One day, in retrospect, the years of struggle will strike you as the most beautiful.”